Have you or anyone you know of had an ACL injury while exercising or playing sports?

70% of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries occur through this planted foot and rapid direction change (pivot) mechanism. Surprisingly, ACL injury is less commonly caused by a contact injury or direct blow to the knee during sports.

How Does ACL Injury Happen?

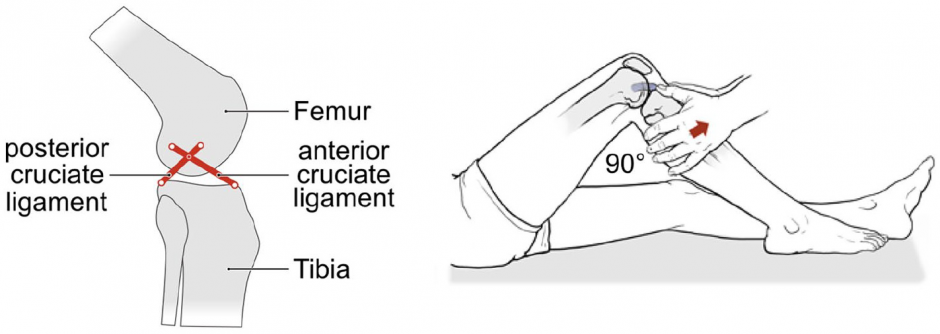

Most often when an ACL injury occurs, the knee is slightly bent. This causes a powerful thigh muscle (quadriceps) contraction. This unopposed muscle contraction with the foot planted, plus the twist required to change direction can result in injury to the ACL.

The ACL runs between the back of the femur (thigh bone) and front of the tibia (shank bone), and is made to resist excessive forward movement of the tibia on the femur (aka excessive knee extension).

Why Does ACL Injury Happen?

It might interest you to know that female athletes have a significantly higher incidence of ACL rupture when competing in similar sports to their male counterparts. Some research suggests even up to 10 times higher injury rates! This is due to both intrinsic or non-modifiable factors as well as to extrinsic or modifiable factors.

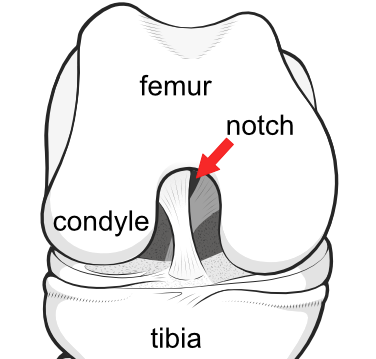

Some intrinsic factors that cause ACL injuries include increased ligament laxity (capacity for stretch) throughout the body, a smaller intercondylar notch where the ACL ligaments run, and greater overall medial knee angulation (knees are angled more towards the midline of the body) than in males.

Some extrinsic or changeable factors include a lack of neuromuscular control when landing from a jump, hop, or suddenly changing direction (supporting muscle groups around the hips and knee do not adequately absorb forces as you land).

In addition, having a ‘quad dominant’ or stiff-legged landing posture, having one leg that is stronger than the other leg, or having impaired trunk control (i.e., lacking postural control due to weakness or imbalances in abdominal muscles) can increase the risk for injury.

Typical Signs & Symptoms of ACL Rupture

There are a few signs to watch out for if suspecting an ACL rupture:

- 50% of the time there is a large amount of swelling in the knee within 0-2 hours

- After an ACL rupture, the athlete is typically unable to complete the game and likely needs help to get off the playing field

- ACL injuries are usually immediately painful, but generally complaints of instability in the knee or feelings of ‘giving way’ become the primary concern of the patient

How to Manage an ACL Injury

There are a few different options to consider when deciding how best to manage your ACL injury. You can opt for surgical reconstruction or non-operative (conservative) management, or you can wait for a few months to see how well your knee is recovering during the rehab process. Recent research suggests that it is possible for an ACL to heal without surgery, however, this will vary depending on the individual.

There is no evidence to suggest that having an ACL reconstruction prevents the development of osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee later in life. A systematic review conducted by Webster & Hewett in March 2022 found that there is a 7-fold increase in the odds of developing knee OA post-ACL injury and an 8-fold increase in the odds of developing knee OA post-ACL reconstruction. In other words, there is a higher chance of developing knee OA if you opt for surgical management.

Surgical management may be necessary to return to certain higher-level sports, however, many factors need to be taken into consideration during this decision-making process. It is best practice to have a discussion with your surgeon to help you determine which course of action is best for you and your situation.

ACL Rehabilitation

Whether you decide to go the surgical route or the conservative route, the goals of rehabilitation of an ACL injury are similar. The Melbourne ACL Rehabilitation Guide 2.0 created by Cooper & Hughes is a fantastic resource that many physiotherapists will use to help guide the rehabilitation process when working with you toward recovery. The process can take 9 months to two years but can vary depending on the level of fitness of the patient going into surgery, differences in someone’s ability to heal and of course the severity of the ACL tear etc.

The most important goals before surgery or right after an injury has occurred are:

- to eliminate swelling

- regain full range of motion of the knee (ability to bend and extend the knee)

- And to regain 90% strength back into the surrounding leg muscles of the injury (in comparison with the uninjured muscles).

It is important to enlist the help of a physiotherapist with this process, as there are specific ways to measure the range of motion, amount of swelling, and comparative strength between limbs which would be difficult to do on your own.

For those that proceed with surgery, the focus after surgery will be similar:

- regain motion

- and regain muscle strength

From there, the program progresses to regaining single-leg balance, working on single-leg squatting with control, and strengthening surrounding muscles (at the hips, knee, and below the knee).

The last phase of recovery is concerned with introducing dynamic hopping and landing exercises, working on improving agility, and regaining full dynamic balance and strength. Once you have completed the program, then your physiotherapist will determine whether you are ready to return to sport using specific return to sport criteria.

I hope that this has given you a better understanding of the mechanism behind your injury, the different ways to manage it, and how a physiotherapist is able to help you navigate the rehabilitation process.

Written by: Tessa Hamilton (Student PT)

Co-authored by: Andrea Reid PT